Oops

For a Better use of this website we recommend to use a pc or a tablet.

Content Warning

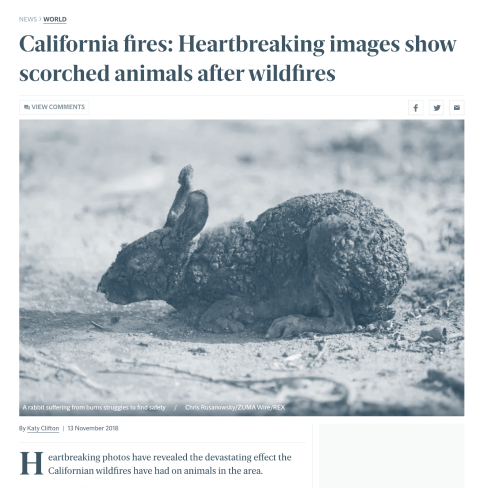

This article contains images of burning/burnt animals and may not be suitable for some viewers.

Tracing online recycling practices

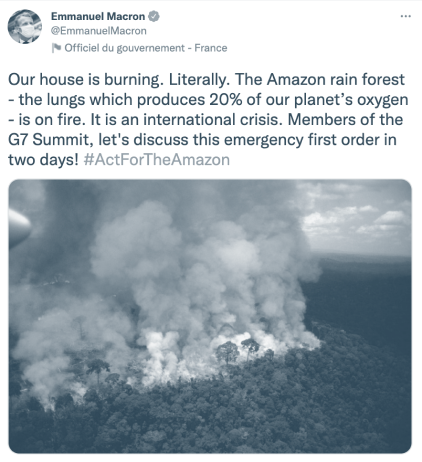

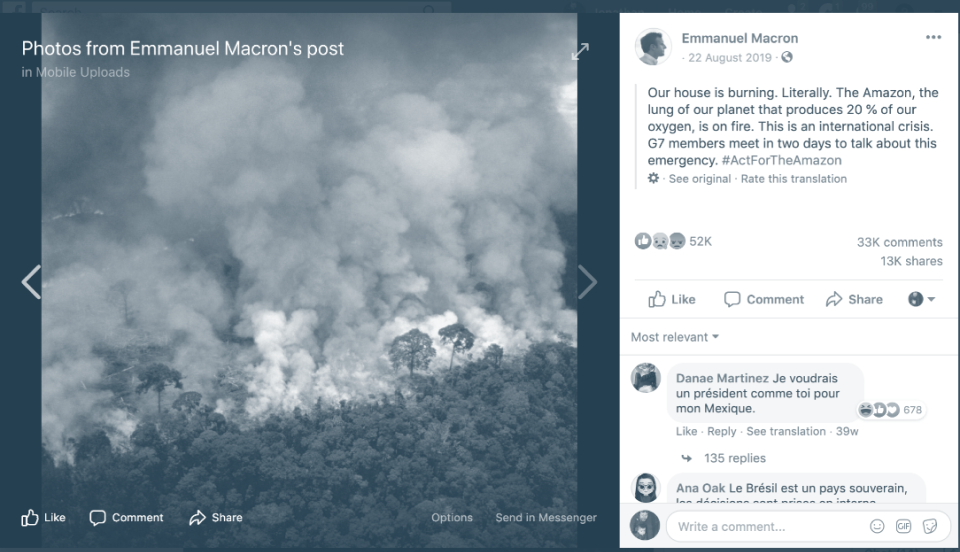

In 2019, the Amazon rainforest fires became a major centre of attention on social media as political actors, celebrities, and athletes including the French President Macron, Leonardo DiCaprio and Cristiano Ronaldo shared their voices, positions and concerns.

While these actors raised public awareness, they also promoted photos and videos from other, sometimes unrelated, past events. These public figures also referred to misleading claims, such as “20% of the world’s oxygen is produced in the Amazon”. While the news media and science communities have contested and debunked these unrelated images and videos online, the contents can be repurposed in different contexts, and can continue to circulate widely online.

This issue story traces the online circulation of recycled media and specific claims related to the Amazon rainforest fires over time.

1 — Generic images from past events are recycled and repurposed to create public awareness

As media and communications researchers have highlighted we encounter a wide variety of"generic images" in media we consume every day. In our analysis, various types of images have been collected showing fires and animals affected from Australia, Africa and Asia.

Animal photos have been mobilised to share concerns around the Amazon rainforest fires

Among the most visible images in our analyses, there were a number of animal photos portraying species which are endemic to the Amazon.

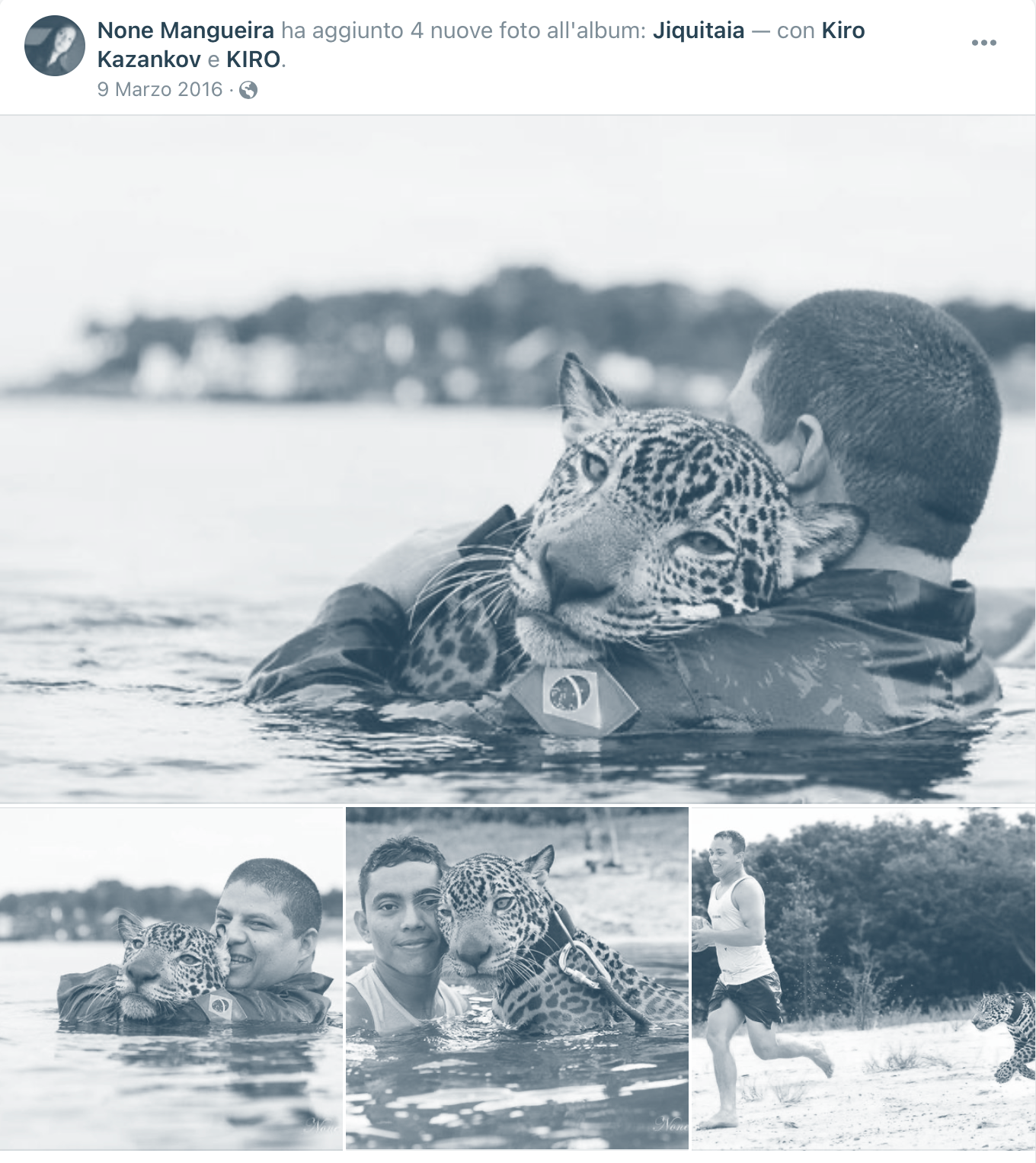

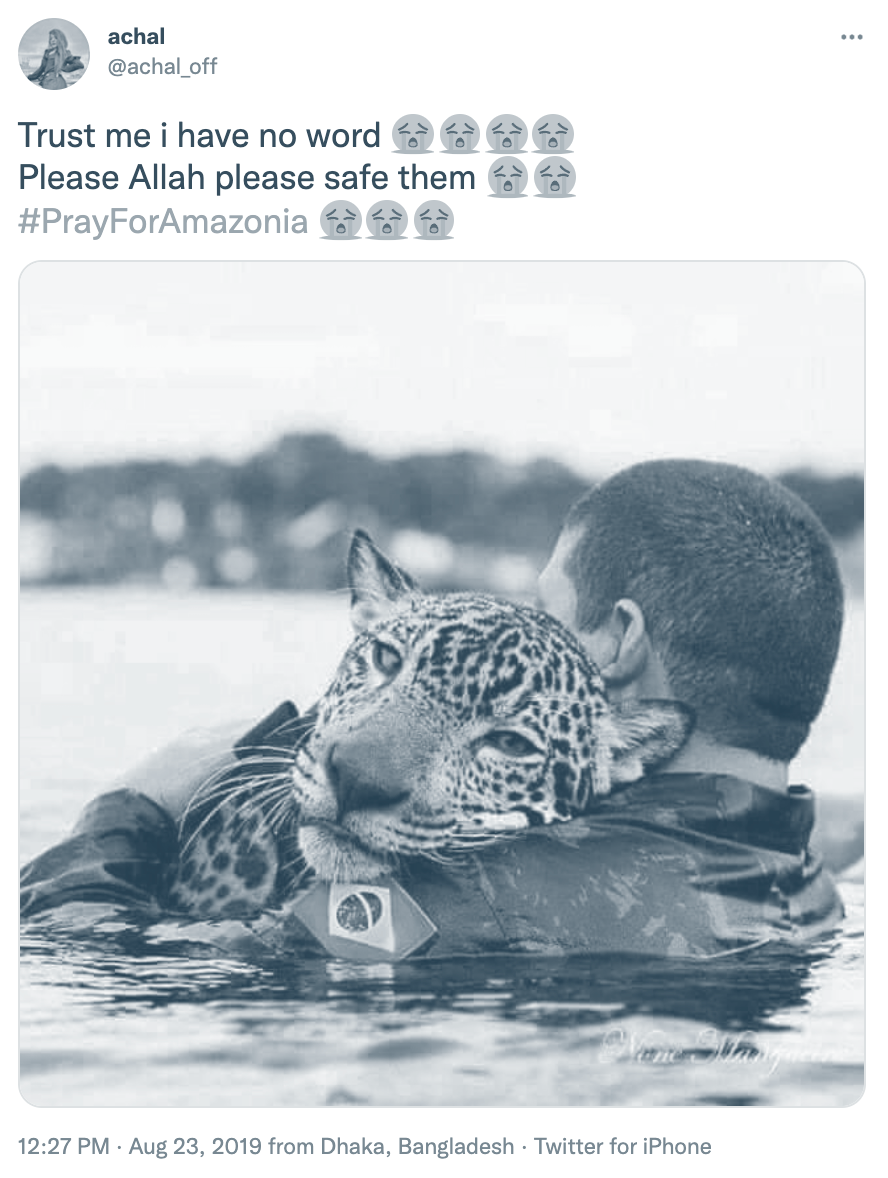

One of the iconic photos was an image of a jaguar rescued by the Brazilian army. Originally taken in 2016 for a conservation project, this photo portrays Jiquitaia, an adopted jaguar held by the army officer that adopted him.

Later in the same year, this photo appeared on social media when Juma, a captive jaguar who became an iconic star during the Rio de Janeiro Olympics, was shot by an army officer at the torch event in Manaus.

In 2019, the same photo reemerged online when the Amazon fires became an international issue.

There were other images from unrelated events elsewhere in the world including those showing a monkey, elephant, orangutan, bear and koala.

Among these animal photos, we identified that the image of monkeys had a similar history to the jaguar image.

When running a reverse image search on TinEye, it is possible to determine that the original image was published in 2017. In the same year, the Independent published the photo stating that the picture was from Jabalpur, India.

During the 2019 Amazon rainforest fires, this image of the monkeys has been modified to form an Internet meme, where the flames have been added in the background.

In the peak period of the Amazon fires, this image has also appeared on the printed edition of the Arab News article. The article also treated the misleading claim of the Amazon producing 20% oxygen as a confirmed fact, while it was highly contested by scientists and journalists.

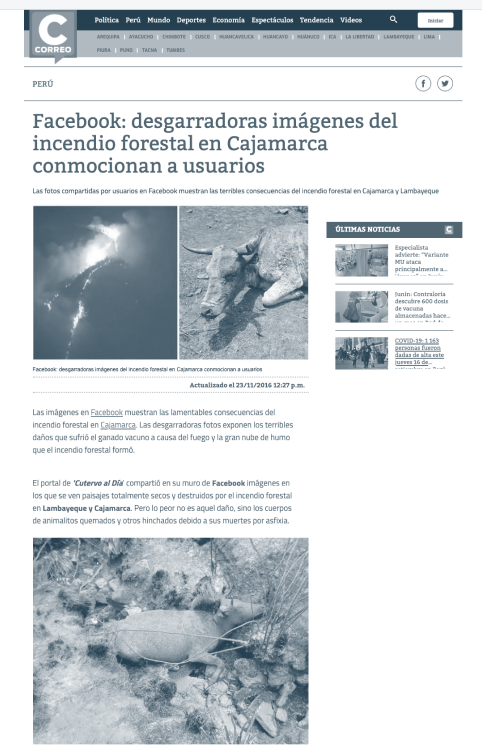

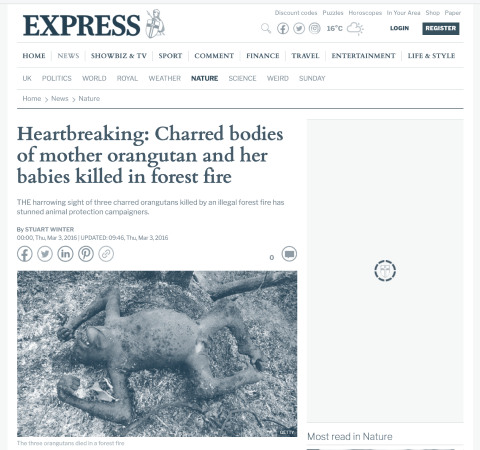

Other animal photos included burnt animals, many of which were from different past events including the fires in Cajamarca, Peru (2016), at the Kutai National Park in the Borneo Island, Malaysia (2016), and in California, USA (2018). The latter two have also emerged on Twitter during the fires at the Bandipur national park in India.

Forest and fire images and videos from unrelated events have also emerged online

Recycled images shared by public figures appeared several times in our analysis. For instance, an old image of burning forests tweeted by Macron has appeared multiple times on Facebook and Instagram.

This image was shot by a photographer who passed away in 2003. The photo posted by Cristiano Ronaldo was from 2013 and taken in southern Brazil.

Leonardo DiCaprio also acknowledged that the photo on his Instagram was from 2017.

There were other forest-related images from various locations in the world.

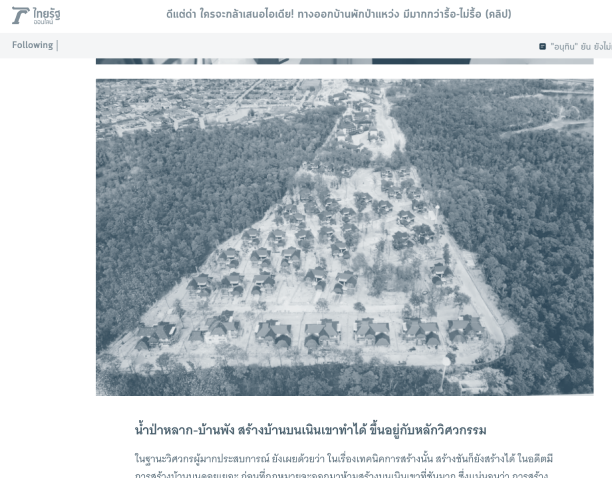

For example, the most retweeted tweet is from 26th August (14340 retweets), and included a photo claiming to show the deforestation issues in Thailand.

When running a TinEye reverse image search, one can see that this photo has also appeared in a news article published on 19 May 2018 by Thairath, which reported about the housing project in Chiang Mai province claiming to affect the forest ecosystems in the area.

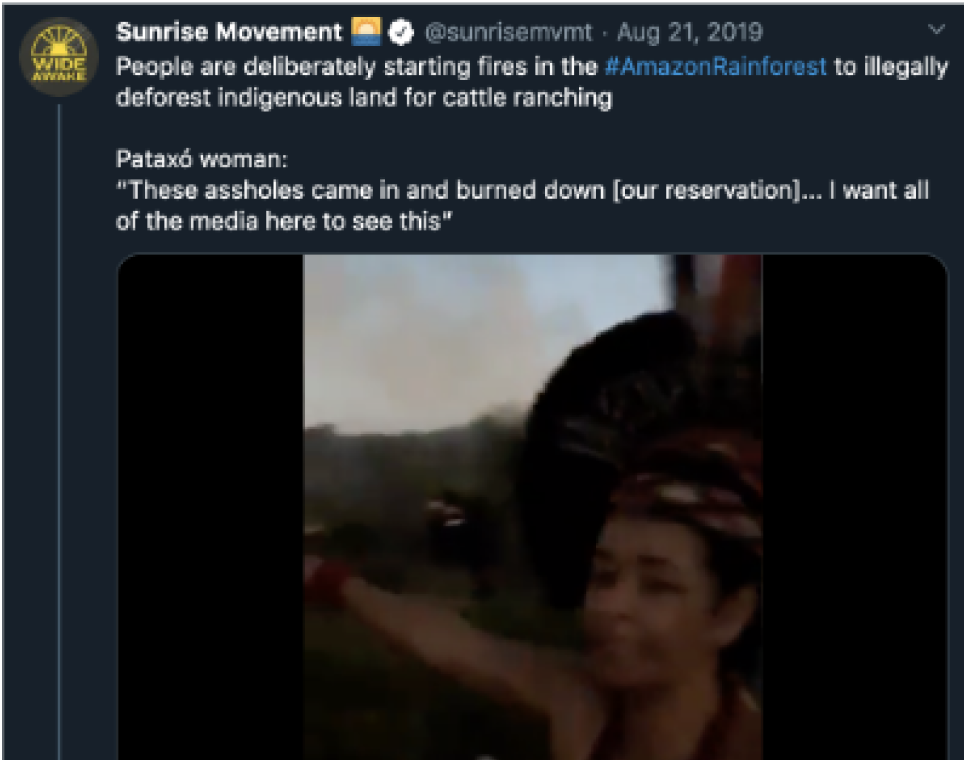

Another example is a fire-related video promoted by the Sunrise Movement on Twitter. Their tweet gathered more than 131K retweets and 157K likes and generated discussion on Twitter. While it was filmed in a place closer to the Amazon, it did not actually come from the affected area.

The tweet included a referral video where a Pataxo indigenous woman is calling for the media's attention on their burning land. Originally from Brumadinho, the Pataxo-Hahahae tribe was directly affected by a dam collapse in early 2019.

The tweet included a source link to a user @kimtaehgukk who tweeted this video on 21 August 2019.

This video was later debunked by the Associated Press as content not linked with the Amazon rainforest fires, but was instead filmed in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais.

2 — Digital platforms and news sites can prolong the life cycle of recycled media and misleading claims

The recycled photo shared by Macron indicates that platforms do not necessarily treat the same debunked content equally.

The famous photo which Macron posted on Twitter and Facebook was taken by a photographer who passed away years before the fires.

In the peak period of the Amazon rainforest fires, the photo was then thematised and modified through the act of tweeting and retweeting. For instance, the copies of original images with minor modification and the screenshots of tagged images on other platforms have circulated on Twitter.

It was also memefied with an image of Moro, a character in the animation film, Princess Monoke.

These images have also been brought together with hashtags like #fakenews which allude to misleading claims.

Beyond the 2019 Amazon fires, these images surfaced online in various contexts, from clean energy investment to peatland fires.

Memefied image — image with other visual elements overlaid or juxtaposed (mainly satirical content)

Copies of original image — with minor modifications (cropped or stretched)

Screenshots of the image — posted in other online spaces (Instagram stories and posts, tweets) with additional textual elements

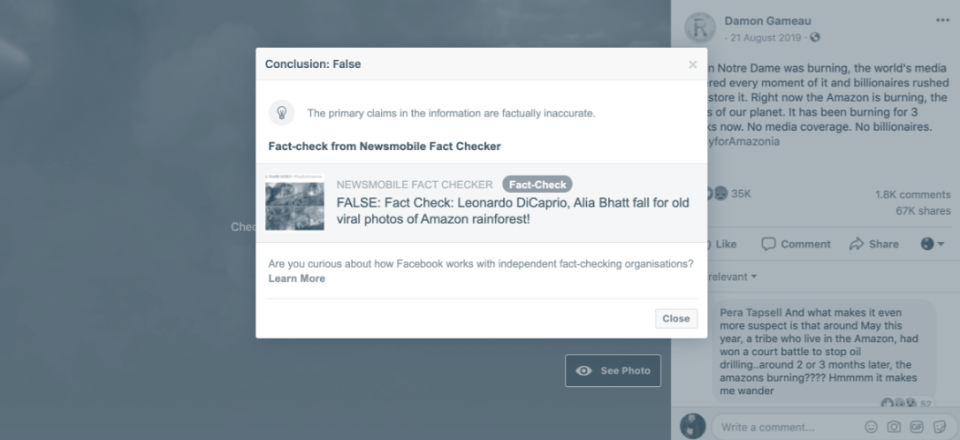

When looking at how the image shared by Macron is treated on Facebook, one can observe that not all versions of the same image are treated equally. For example, one widely circulating version of an image on Facebook has a warning from fact-checking organisations, whereas the same image posted by Macron contains no such warning.

This example indicates that a potentially misleading image can have a longer life despite verification labelling and fact-checking practices on digital platforms. Their policies and algorithms can therefore prolong the lifespan of potentially misleading content online.

News articles

Statements and claims, including misleading ones, can also surface even if they are widely debunked online, especially when news articles continue to cite a misleading claim without correction.

As we looked into the media articles promoted with the 20% oxygen claim on Twitter, a number of articles published by CNN, Cnet, Global News and Arab News have surfaced. All of these articles treated the misleading claim as a confirmed fact, and did not add any corrections to the published stories.

CNN particularly stood out as their articles consistently supported the claim. When looking at the URLs embedded in all the media articles in our sample, there were 26 unique URLs directed to the CNN website. Among these URLs, 8 stories explicitly promoted the misleading claim.

Research indicates that images "do well" on social media. The professionalised use of stock images in social media posts and news coverage is widespread amongst journalists and media organisations, especially where visuals accompany breaking news stories.

Our analysis indicates the prominent role that stock and "generic" images play not just in news coverage but also more widely in online mobilisations around environmental issues. While images can be "fact-checked" and it can often be assumed that an image is being presented as a literal representation of events, the re-purposing of such images is not in itself inherently problematic. Image reuse is not only part of professional image editorial, but also digital culture and social media user practices (e.g. making memes from common images and stock photography).

The politics of recycled media, stock photography and generic images in relation to environmental issues deserve careful attention and interpretation. Our research suggests the value of more differential analyses about what such images do and more situated accounts of the meanings with which they are invested, rather than being assumed to default to a more literal, representational mode.